Why Writers Need Rituals: An Invitation to Dream

On the psychology and neuroscience of writing rituals

Do you have any New Year's resolutions or intentions involving writing?

If so, you’ve probably struggled to transition into the sort of mental state where ideas flow painlessly – even joyfully.

Several pervasive mental states of modern life interfere:

You're stressed, running around and mentally chattering, feeling you’re inevitably falling ever further behind.

You're overwhelmed by everything else you're not doing right now, and perhaps afraid of missing out.

You feel dull and fatigued: the inevitable crash after the previous two states.

You're thinking only about measurable aspects of the Final Product (number of engagements on social media, new followers, dollars earned, etc.).

When you write every day, you will constantly confront these, and other, difficulties getting started.

Writers have long solved the problem by creating a ritual around writing.

Some invent famously bizarre rituals. For example, Schiller wrote with rotten apples inside his desk. Dame Edith Sitwell was said to lie in an open coffin before sitting down to write.

I've described such idiosyncratic rituals and explained why they help elsewhere. However, the topic came up only briefly, in the context of advising neurodivergent people on organizing to support their creativity. Here, I'm addressing people of all neurotypes, because anyone can benefit from a writing ritual.

Yet, many writers, unfamiliar with the concept, struggle unnecessarily.

How do rituals work? Why do writers – an idiosyncratic bunch – gravitate to something so regimented, so often used to maintain the social order?

Psychology and neuroscience offer some answers.

These insights can benefit any writer. Sometimes, we fumble our way towards a ritual that works for us, discovering what feels “right” but not knowing why. Understanding how and why rituals work can help us intentionally develop our own.

Why Writers Need Rituals

The cumulative purpose of doing these things the same way every day seems to be a way of saying to the mind, you’re going to be dreaming soon. – Stephen King

Have you noticed how avidly writers devour information about others’ writing process?

Writers’ magazines interview famous authors about their habits, while how-to books feature anecdotes about the same. Eavesdrop on a conversation between writers and you'll hear them either complaining about their struggles with process or swapping tips.

Why do writers seek information on other writers’ writing habits the way many people devour gossip about celebrities’ personal lives?

Because writing is hard, in a particular way.

Like running, writing involves much time invested in the process of creating, and very little enjoying the final “payoff" – especially for those who insist on writing books.

Moreover, writing involves letting go of control and observing our thoughts. Many people find it painful to sit alone with their own minds without distraction.

Yet, one must get in touch with one’s own mind: first, to generate ideas; second, to monitor one’s state and needs while writing.

For example, when I feel stuck, I ask myself, "is it because…”

…I have a problem to resolve? (For fiction: a plot or character question; for nonfiction, a logical gap or a counterargument I can't yet answer).

…I need to learn more about my audience?

…I can't think of enough ideas?

…I'm overwhelmed by too many ideas?

…I dislike what I've written so far?

…I've lost interest in the project?

…I'm afraid of what other people will think?

…I'm afraid of failure or success?

…I'm distracted by parts of my life unrelated to writing?

Finally, writing challenges most people because it requires both divergent and convergent thinking. Worse, the proportions change as a project progresses. Most people prefer one or the other, and find it difficult to flexibly shift between them.

Divergent thinking helps us generate new ideas. It also reveals new implications while editing, perhaps leading us to rewrite. It draws on the unpredictable, capacious systems that constantly combine and recombine ideas beneath our conscious awareness.

Convergent thinking keeps us focused. It also helps us present ideas clearly and in logical order. It enables us to choose the appropriate length and level of detail for our audience. Convergent thinking consists mainly of executive functioning skills.

(That’s why writers with ADHD – who often have strong divergent thinking – excel at generating ideas. However, executive dysfunction disrupts our convergent thinking. That makes our writing too long and sometimes confusing. It can also prevent us from finishing projects).

Fortunately, humans can apply a powerful tool: ritual.

What is a Ritual?

What comes to mind when someone mentions “ritual?" Do you imagine a religious service at home?, a coming of age ceremony abroad?, Americans saluting their national flag?, icebreaker activities? Do you think of "ritualistic” behavior like the hand washing of people with obsessive compulsive disorder?

Perhaps you've studied anthropology and are shaking your head, because ritual isn't just one thing you can define simply in a short blog post. (At risk of over-simplification, I’m going to try anyway).

Essentially, a ritual is a series of actions, consistently and intentionally performed in the same way in the same place at the same time, for a particular purpose.

Rituals create a separate time and place for a purpose that requires an unusual mental state that people normally struggle to enter. They encourage that state of mind in two ways.

First, rituals include cues that support achieving the desired mental state. For example, some cultures induce a trance using chanting, music and dance, or hallucinogenic substances.

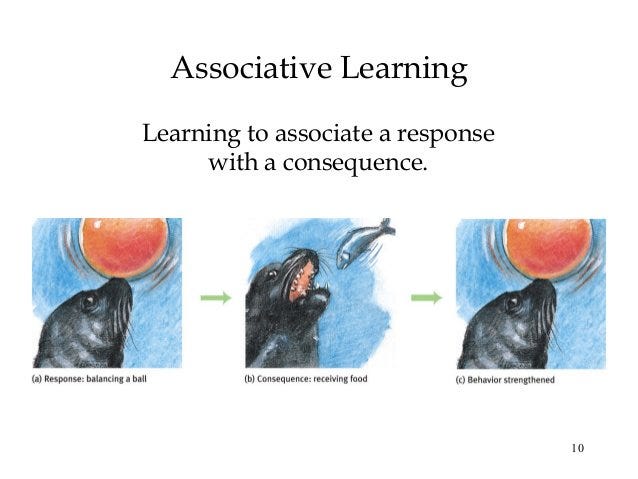

Second, rituals work through repetition. We learn to associate the place, time and sensory cues of the ritual with the mental state. Eventually, experiencing these cues prompts us to enter the state almost automatically.

For example, when we smell incense and hear familiar chants in a religious service, our thoughts may automatically turn to awe and gratitude.

Rituals can be observed worldwide, for many purposes. They have probably existed at least as long as homo sapiens. What makes rituals such a powerful tool?

How Rituals Work

Rituals draw on the powerful associative learning processes that all mammals share.

The world constantly presents people with associations between infinite combinations of objects, words, actions, places, and time. Whether or not we consciously recognize these relationships, we continually observe them and feed that information into dedicated brain circuits that support specific types of action.

Those neurons change their firing pattern, responding ever more consistently to the trigger. Eventually, new synapses grow, linking these neurons, which further cements the trigger-response association.

Ultimately, we learn to link something we perceive (a “trigger”) with a specific action. When we observe the “trigger,” we perform the action immediately and automatically.

Associative learning comes in several varieties. Mammals notice cues in their environment that predict:

danger (“fear conditioning”);

aversive outcomes (unpleasant experiences, such as a puff of air hitting the eye in eyeblink conditioning experiments);

rewards (“appetitive conditioning”);

outcomes that are especially important to us;

and more.

Each type of associative learning relies on specific brain regions. For example, changes in the amygdala underpin fear conditioning. The hippocampus forms associations involving spatial relationships (such as moving through a maze) or multiple senses (such as sight plus hearing). The cerebellum appears to support aversive conditioning.

Through associative learning, mammals learn behavior that runs the gamut of complexity and meaningfulness. Rodents and rabbits learn to blink their eyes at a specific time; monkeys learn to look or reach in a specific direction. Babies use the complex statistical associations between words and words, and between words and the world, to learn language.

Children and adults can learn extremely complex associations. They can link names with faces, nonsense sounds with symbols invented by researchers, and more.

When associative learning systems go awry, they can contribute to addiction and PTSD. For example, traumatized people undergo fear conditioning that produces intense, involuntary emotional reactions to otherwise innocuous words, places, and things (“triggers").

Traumatized people’s reactions are an extreme example of how all humans react: We may not be conscious of either the trigger or our own behavior before we act. That may surprise most people, because they rarely observe their behavior that closely. They rarely need to, as their reactions are usually considered appropriate and proportionate to the situation.

Associative learning can also disrupt our lives in subtler ways. Ironically, it can hamper studying, because we unintentionally form associations between the place we studied and the material learned there. Suppose we always sit in the back left corner of the classroom. If we also sit there during tests, we readily remember the information. If we instead sit on the front right, we might struggle to recall it.

The same principle explains state-dependent learning: We remember information best when we retrieve it in the same physical and mental state in which we learned it. My college psychology professors advised students not to study drunk – because then they could only fully access the information by taking the test drunk, too.

State-dependent learning affects more than just imprudent college students: the same idea applies to sleep deprivation.

Despite these drawbacks, associative learning makes a powerful tool when used deliberately. For example, we can harness it using habits and rituals — such as the rituals writers use to ease their way into a creative state.

That's one reason why writing rituals can be so powerful: they draw on ancient, built-in associative learning processes.

(ASIDE: Of course, humans generally have more than one reason for their behavior. Rituals surely help writers for other reasons, too).

Do you have a writing ritual? How do you tell your mind it's time to dream?

I’m curious what and if other writers have rituals they’d be willing to share. Or what rituals they’d like to implement. I’ve heard of some writers lighting a candle to write.