What the government needs to know about autism: taking back the policy agenda from Autism Speaks

Autism Speaks is back to its usual message: (trigger warning) autistic people are "missing;" they tear their families apart; they make their parents' lives uniformly sick and miserable so that they're "existing" rather than "living"; they burden society; and their lives aren't worth the cost of supporting them.

Their latest call to action caused their sole autistic board member, John Elder Robison, to quit in disgust.

Unfortunately, this time they're not content with spreading their message of hate and fear to the public at large. They want to use this message to guide public policy: specifically, they're meeting with all 535 members of Congress right now to set the agenda for a new national policy on autism.

They call themselves "Autism Speaks," but they haven't invited any autistic people to participate in their effort and some claim they've actively discouraged autistic people from doing so.

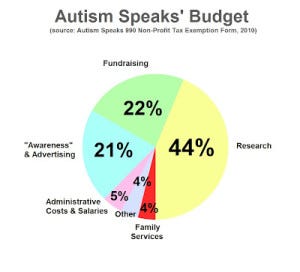

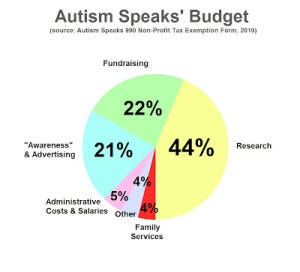

Given their own track record, Autism Speaks should not be setting funding priorities: only 4% of their funding goes to services for families.

Below: budget from Autism Speaks's tax exemption form, 2010. Note that they spend more on fundraising, "awareness" ads, and administrative costs than on research and services combined. Do we really want a government plan based on these funding priorities?

For the first time, large numbers of non-autistic parents have joined autistic adults in denouncing Autism Speaks. They point out that Autism Speaks not only hurts autistic adults, but hurts them and makes parenting their children more difficult. One described her son reading Autism Speaks' call to action over her shoulder (unbeknownst to her) and asking, "Mom, do I make you ill?" A few of the parents who have spoken out so far:

But I fear that denouncing Autism Speaks isn't enough. The government is considering setting policy that might determine the services available to the autistic people in our lives, and the sort of research that will be funded. We need to send an alternative, positive message detailing what a helpful government autism policy would look like. Some ideas follow:

1. Understand that autism is a disability, like dyslexia or deafness, not a disease like cancer. The bad part of this is autism comes with a person at birth, and influences how they think, feel, move, and perceive for life. The good news is that the degree to which autism keeps a person from doing things stems from a combination of their own weaknesses and the degree of support available to them. Just as deaf people or people with dyslexia can work and achieve other goals with appropriate accommodations, so too can autistic people. Teaching autistic people skills and accepting a certain degree of quirky behavior (such as flapping one's hands or wearing headphones in public) can help them accomplish more and live happier lives. Autism may be lifelong, but it isn't a life sentence.

2. Understand that autism isn't always expensive. Some people need nothing more expensive than headphones, dark glasses, and acceptance. Others need 24-7, lifelong care or extensive medication. Because autism is a spectrum condition, most will fall somewhere in the middle. For some, support will allow them to hold down a full time job and/or raise a family. For others, it won't.

3. Listen to autistic people and focus funding on priorities shared by them, parents, and clinicians. Autism affects people along the full range of intelligence and verbal ability. While most have some degree of difficulty with finding words or processing what other people say, many can share their thoughts via speech, writing, or typing. Many have thought a great deal about what helps them and what hurts them and why, and are eager to share their thoughts. Many identify with younger autistic people whom they've never met, and want them to live better lives.

Because autism has certain commonalities regardless of the severity of the disability, the most verbal and insightful people with autism often share experiences with the most nonverbal and severely disabled, and can often give parents and clinicians information they wouldn't otherwise have had. Difficulty speaking, sensory overload or meltdowns, poor executive function, self-injury, even choking on a glass of water--all of these affect people deemed "high functioning" as well as those called "low-functioning." Thus, listening to those who can speak to us can help us better understand those who can't.

Due to limited funding, and the fact that autism affects everyone, funding priorities shared by autistic people, parents, and clinicians seems likely to yield the greatest benefit. This seems self-evident enough not to explain further.

4. More funding for services. One area where autistic people, parents, and clinicians all agree: there aren't enough programs and they're not well-enough funded. The push to develop and fund early intervention means that such program do exist in many areas. However, support is less likely to be available for teenagers and adults, and for both the most and least severely disabled.

5. More support for teens and adults. Autism doesn't vanish at adulthood, as Autism Speaks and the media would have you believe; yet services often do. Adults with autism and other disabilities are underemployed, less likely to work full time, and earn a lower salary. Yet many could achieve greater independence if they had access to coaching in etiquette on the job, job skills, managing money, and so on. At the moment, only parent-founded companies such as Specialisterne and Project Dandelion are filling the need for jobs for autistic people. Such companies find that the intense focus, technological aptitude, and tolerance for repetitive work exhibited by many on the spectrum can become assets on the job. Both autistic adults and their parents say housing is also a problem for many on the spectrum.

6. Services should reflect that most will be capable of more independence than possible in an institution, but not all may achieve complete independence. Given the spectrum nature of autism, there should be options between full independence and living in an institution, but few exist at present. Housing options, part-time caretaking options, and other services should enable many degrees of partial independence.

7. Basic research should focus more on how autism works (from biochemistry up to how people learn), rather than how to prevent it. Knowing what factors increase autism risk doesn't help autistic kids or adults live better lives, and it doesn't help parents deal with the challenges of autism. On the other hand, knowing the biochemistry of autism might help with developing drugs to manage the anxiety, emotional overwhelm, meltdowns and self-injury affecting many on the spectrum. Knowing how autistic people process sensory information may help us, and them, with managing their exposure to sensory stimulation, which in turn may help them behave better and achieve more at school and in the workplace. Lastly, knowing how autistic people learn will help with developing more effective educational programs.

8. More funding for applied research, especially on educational and intervention programs at all ages. A lot of research right now focuses on early diagnosis and intervention, which is great. But even people diagnosed late in childhood--or as adults--can learn new skills and improve their quality of life. For example, a large percentage of children who still weren't speaking at four years old were speaking by age eight (Wodka, Mathy & Kalb 2013). Temple Grandin reports that her speeches at age 60 are better than those at age 50, and she's not the only autistic adult to report learning new skills (particularly social ones) as an adult. My own brother wasn't diagnosed until third grade, supposedly "too late." At this point, a late talker, he had difficulty understanding metaphors and figurative language, had frequent meltdowns, was constantly anxious, had difficulty writing, and couldn't "cross the midline" (bring an arm or leg across the middle of his body to the opposite side). Now he's a great writer and sophisticated user of figurative language, rarely melts down, is less anxious, can cross the midline effortlessly, has earned a commendation from the National Merit Scholarship people and is applying to college this year. I think a combination of speech and language, motor and social skills therapy; teachers who loved him; and huge effort on his part made the difference.

9. Autistic people (and many parents) prioritize the following research. Consider supporting it. http://www.forbes.com/sites/emilywillingham/2012/11/01/what-do-autistic-people-want-from-science/

10. Developing positive programs that use individuals' strengths to compensate for or work around their weaknesses. Most autistic people aren't savants like Rain Man or geniuses like Einstein, yet many have at least relative areas of strength and interest. Successful autistic adults, such as Temple Grandin and John Elder Robison, argue that following their strengths and interests was the key to their success; the mother of the autistic young math genius Jacob Burnett argues the same in The Spark. Early on, Temple Grandin's mother noticed that Temple constantly drew horse's heads, and encouraged her to draw more things. Today, research studies are starting to support teaching social skills and other difficult tasks using a child's special interests.

11. Most services are provided by local organizations, often not-for-profits; support them. In my area, many families access support through Easter Seals, particularly its therapeutic school; The Autism Program (TAP), and even more locally, Have Dreams. These organizations spend most of their budget on serving autistic children and teenagers rather than on fundraising and salaries, and deserve government support.

We need to present a better alternative to what Autism Speaks is proposing. What positive, actionable messages would you send the government?