Meta-Analysis 101: How to Develop a Research Question and Decide What Evidence is Relevant

Learn the process of doing a meta-analysis by designing one with me.

We’ve seen that meta-analyses are a way of using statistics to discover “what the research says” about the size and direction of a cause-and-effect relationship. To understand meta-analyses more deeply, let’s walk through the process of doing an imaginary meta-analysis ourselves.

We’ll look at a real meta-analysis, which investigates the effects of meditation on people with ADHD. Imagining ourselves in the authors’ place, we’ll examine how the researchers developed their question. We’ll narrow the scope of the question with them, deciding which evidence to include and which is irrelevant. We’ll consider why the authors made the choices they did, and what else they could have done. There are times when I would have made different choices than the authors, and I’ll explain why.

Doing a meta-analysis involves these 5 steps:

Choose a research question.

Search for all the potentially relevant research articles.

Exclude articles that are duplicates, unusable, or irrelevant.

Extract the data you need.

Perform statistical analyses.

In this post, we’ll focus on the first 3 steps. We’ll develop a research question and discover what evidence bears on it. In a future post, we’ll tackle the process of making decisions about statistical analysis: choosing how we’ll assess what the research shows.

Let’s get started!

1. Define a Research Question

We might start with a broad question, such as: “Does meditation help people with ADHD?"

That sort of question is fine in everyday life. However, looking more closely, you’ll notice it’s vague. What do we mean by meditation? Help in what way? In a meta-analysis, our question must be specific enough to quantify.

In health research, that means defining our PICO:

Population,

Intervention,

Comparison, and

Outcomes.

Population means who we’re studying (in this case, people with ADHD). Intervention means how participants are treated: what experimental condition they undergo or what therapy they receive (in this case, meditation). Comparison or control means what meditation is being compared with. Often, that means whatever constitutes “treatment as usual" in the participants’ communities. Finally, Outcomes means what result we will measure: what we expect the Intervention to change.

PICO is typically used for health research, but we can adapt it to studies where no one receives any medical treatment. Here, Intervention means the experimental condition, while Comparison means the control condition. For example, if you want to know whether a font designed for people with dyslexia actually helps them read faster and more accurately, your “Intervention” would be exposure to text in the new font, while your “Comparison” would be the same words in a frequently used default font, such as Arial or Times New Roman.

Population

First, what do we mean by “people with ADHD?” Sometimes researchers say “people with ADHD,” but they actually mean a subset of that large group.

What ages will we study? Children, adolescents, adults, or all ages?

Which type of ADHD will we study? There are three: Inattentive, Hyperactive/Impulsive, and Combined. Are we interested in how meditation affects one or all of them?

For example, if you’re wondering how meditation affects attention, you might focus on people with Inattentive and perhaps Combined Type ADHD. However, if you’re interested in how meditation affects emotion regulation or impulsivity, you’d favor those with Hyperactive/Impulsive and perhaps Combined Type.

Do we care if study participants, like most people with ADHD, have co-occurring diagnoses? Many people with ADHD also have mental illnesses, learning disabilities, or chronic physical conditions like migraines or allergies. Do we think other conditions, such as depression, are potential confounds? If so, we would only use studies that exclude participants with depression.

The “purer” your ADHD sample is, the better you can judge whether meditation is improving ADHD symptoms specifically, or indirectly, by generally improving health and well-being.

Unfortunately, the purer your sample, the smaller it will be, and the less it will represent the “typical” person with ADHD.

Intervention

What do we mean by meditation?

Many types of meditation exist, using different practices to encourage different mental states. Some emphasize spirituality; others, physical and mental health. You might:

chant mantras,

fill your heart with love and kindness,

visualize your thoughts as leaves flowing down a stream,

attend to the feelings in your body,

focus on your breathing,

concentrate on a sound, or

simply observe your mind as it naturally wanders.

Which practices seem especially likely to address the challenges of people with ADHD?

Zhang’s team chose to cast a broad net, considering every attempt at treating ADHD with any kind of meditation. They wanted to establish what effect, if any, meditation in general might have.

Some people consistently practice meditation at home, although people with ADHD may be less consistent. Will our meta-analysis include studies of this sort of informal meditation, or is that too uncontrolled? Zhang’s team only included meditation that was organized and led by a trained professional.

Meditation is sometimes used as a piece of a larger therapy program, such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) or Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT). Will we include studies of such programs, or are we interested only in the effects of meditation alone? Including broader therapy studies will give us more data, but would make it unclear whether, and how much, meditation contributes to the effects. That’s what Zhang’s team did.

I, personally, would leave out such studies out, to make the meaning of the meta-analysis results clearer.

Which would you have done?

Outcomes

Suppose we suspect that meditation benefits people with ADHD. How might it help them?

We’re asking about a mechanism: what does meditation cause to happen in the minds and brains of people with ADHD?

Thus, we will consider:

how meditation works,

how ADHD people’s brains work, and

what outcomes matter most for people with ADHD.

Based on how meditation affects the general population, and my own experiences doing several kinds of meditation, I suspect that it improves people’s awareness of their attention and perhaps their ability to control it. Thus, I expect meditation will reduce inattentive ADHD symptoms.

These symptoms are usually measured using self-report questionnaires. However, I would look for further evidence that attention has improved, such as better scores on the standard measures of attention used in research and neuropsychological testing.

I also think meditation increases awareness of, and control over, emotional reactions. That might translate into reduced hyperactive/impulsive ADHD symptoms. We might also see better scores on standard lab and neuropsychological measures of “emotion regulation” and “inhibition”.

When choosing outcome measures to study, values also come into play. As a person with ADHD, I care about more than just reduced symptoms. Does meditation improve mental health? Quality of life? Quality and quantity of social relationships? Work performance?

Unfortunately, Zhang’s team did not include any of these important outcomes in their meta-analysis. They may have wanted to reduce their scope, either for practical reasons or to minimize the statistical problem of multiple comparisons. However, I still would have included at least one measure related to mental health, functioning, or quality of life.

Next, how will your outcomes be measured? You could choose any or all of these:

Observation

Questionnaires

Standardized testing

These choices lead to further questions:

Observation: What will participants be observed doing?

Questionnaires: Which questionnaires? Who will fill them out: the participant, someone who knows them well, or both? What will you do if informants disagree?

Standardized tests: Which tests?

Choosing your outcome measure(s) allows you to quantify your hypothesis.

Researchers don’t make these decisions in a vacuum. However we define our research question at the beginning, our answers will change as we discover what research has actually been done. The research question will narrow. It might also take a new direction.

For example, an outcome that interests us may have been ignored – forcing us to choose a different outcome measure.

Alternatively, the literature could focus on an outcome that we haven’t considered at all. We might decide to incorporate it into our meta-analysis.

Important segments of our population could be neglected. For example, until recently, there was a lack of research on adults with ADHD. That might limit the population we consider.

Ultimately, Zhang’s team chose the following PICO:

I would have chosen:

What PICO would you choose?

2. Find All Potentially Relevant Data

As researchers develop their question, they search for all available evidence. To prove that they’ve found all the relevant data, they must cast a wide net. The search process is surprisingly complex.

For example, finding all published literature typically requires using multiple databases. Using just PubMed or Google Scholar isn’t enough.

In addition to published literature, labs generate copious unpublished data waiting, perhaps indefinitely, to be written up. This work is called “gray literature.”

Student master and PhD theses, technically unpublished, may also be relevant.

Thus, doing a meta-analysis involves writing to other researchers, asking for gray literature. (For those interested in developmental psychology, the Cognitive Development Society’s cogdevsoc listserv is a great place to ask).

I’ll spare you the details, but the researchers doing the meta-analysis should provide them in the Methods section, clearly enough that you could do the same searches yourself.

3. Decide Which Articles to (Not) Use

Researchers don’t use every article they find.

First, some of what they turn up is simply unusable, such as

Duplicate articles (for example, a pre-print version and the final published version; or the same article on both PubMed and an author’s website).

Articles only available in a different language the research team can’t understand.

Articles where only the Abstract is available, and no quantitative results can be found.

Typically, people doing a meta-analysis start searching while their research question is still broad and vague. As they refine their question, they put aside studies that no longer fit, such as:

Articles using different participant demographics (participants are children and you’re researching adults; or, some participants have co-occurring conditions you see as a confound).

Articles using different outcome measures (for example, articles measuring working memory when you’re interested in quality of life).

When researchers “exclude” such studies, they must carefully document and explain their choices.

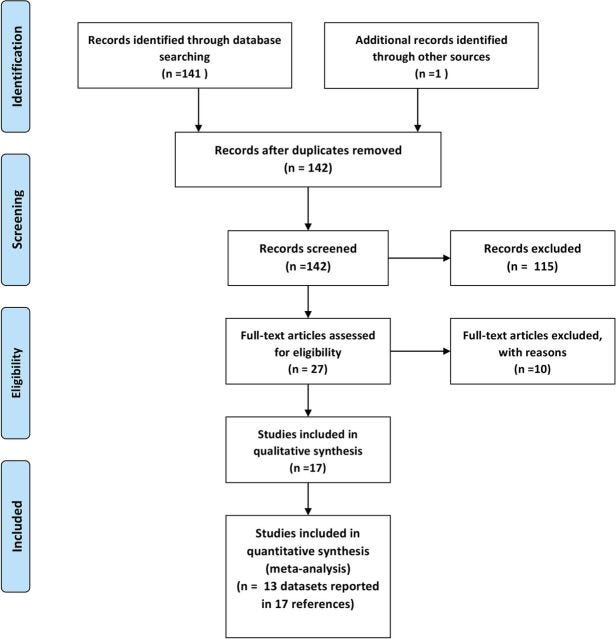

Each published meta-analysis includes a flow chart that follows specific guidelines. These charts explain how many studies were excluded, in what order, for what reasons.

The “exclusion criteria" are the unsung heroes of a meta-analysis.

What Now?

We have now completed the first 3 steps of a meta-analysis! We’ve developed a precise research question and found the relevant evidence.

We’ve finished the most time-consuming parts of the process.

Next, we’ll extract the important information from the studies and decide how best to statistically analyze it. That’s a topic for another post. Stay tuned!

___

Did anything about the meta-analysis process interest, surprise, or confuse you? How would you approach that question about meditation and ADHD? What would you ask instead? Hit the button below to share your thoughts.

great summary, thank you!