The Brain Evolved from the Inside Out

Well…the vertebrate brain did, anyway.

Behold, the human brain: the culmination of a long evolutionary process.

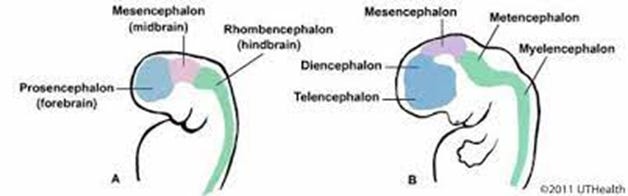

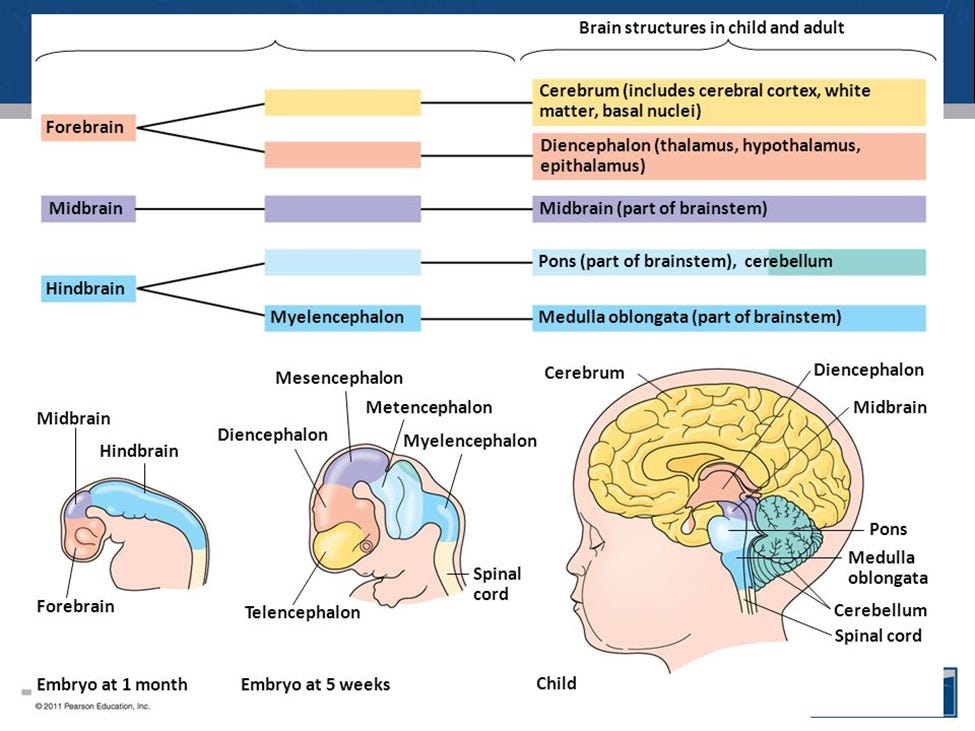

In order to understand how the human brain evolved, we need to be able to compare landmarks. So, here’s a quick overview of the anatomy.

From bottom to top, evolutionarily oldest to newest, human and animal brains can be divided into five sections.

Medulla Oblongata (Myelencephalon): Controls autonomic functions, such as breathing, heart rate, and digestion. You would die without it.

2) Pons and Cerebellum (Metencephalon): Coordinates movement and other brain functions; conducts sensory information.

The medulla and pons together make up the “brain stem,” which is necessary for survival.

3) Midbrain (Mesencephalon)

4) Thalamus and Hypothalamus (Diencephalon): The thalamus is often conceptualized as a “relay station” for sensory information. The hypothalamus controls autonomic functions, such as appetite.

5) Cerebral Hemispheres and Subcortical Structures: Basal Ganglia, Hippocampus, and Amygdala (Telencephalon): The cortex does most information processing, including perceiving, thinking, and using language. The other structures include the limbic system, which regulates emotions, memory, and learning from emotional experiences (such as avoiding a food after it makes you sick).

The Subcortical Structures evolved earlier than the Cerebral Hemispheres and the two should really be placed in separate categories, for reasons I’ll explain later.

The names all contain the Greek word “encephalon,” which means “brain” (or literally, en-, “in” and cephalon, “the head”). A writer at Rice University suggests the mnemonic that the “telencephalon” is near the “top.”

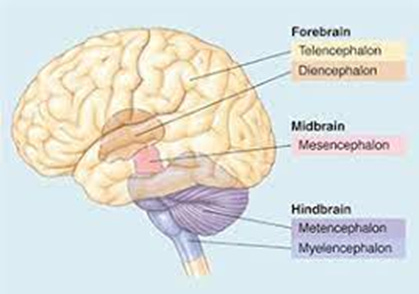

These regions can be divided up even more simply, as follows:

Forebrain: the telencephalon and diencephalon

Midbrain: the mesencephalon

Hindbrain: the metencephalon and myelencephalon

We can see these parts of the brain most easily in developing human fetuses, as shown below:

The fetus’s brain develops in the same order that the regions evolved. Watching one grow is a pretty neat way to study evolution without a time machine!

Now that we have the anatomical landmarks, we can track how they evolved in animal and human brains.

A Brief History of Brain Evolution

The image below shows the brains of various types of animals in the order in which they branched off the evolutionary tree (oldest at the bottom, most recent at the top).

To clarify the terminology, the “medulla oblongata” is the medulla, and the “cerebral hemispheres” are the “cerebral cortex.”

Remember that the medulla and cerebellum are part of the hindbrain, while the cerebellar hemispheres (telencephalon) are part of the forebrain. The pituitary gland, optic tectum, and olfactory bulb are relatively early-evolving parts of the forebrain.

Notice that the evolutionarily oldest brain, the lamprey’s, consists mostly of the brain stem. The only parts of the forebrain present are the optic tectum, to process visual stimuli, the olfactory bulb, to process smells, and the pituitary gland, to regulate growth. The cerebellum isn’t present at all.

The cerebellum begins to develop among amphibians and sharks, and grows over evolutionary time. In birds and mammals, it reaches its familiar shape and texture. At this point, the hindbrain is fully developed.

The cerebral hemispheres grow out of the olfactory bulb and get bigger over evolutionary time. Sharks and bony fish have small cerebral hemispheres. In birds and especially mammals, the expanding cortex grows around, and covers, other regions.

The visualization below shows the same processes, with evolutionary time advancing in a counterclockwise direction and slightly different labels. The animals on the left side of the chart are all types of fish.

Notice the same evolutionary changes at work:

The medulla develops first.

The cerebellum is an early addition that is well developed in birds and mammals.

The forebrain develops relatively late.

The cortex, or telencephalon, gradually grows to surround everything but the cerebellum.

Overall, the brain develops bottom to top and inside to out.

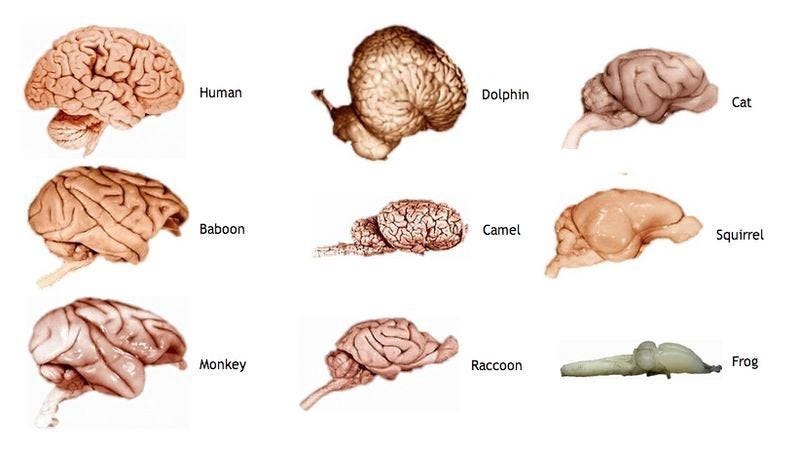

The brain did not stop evolving once mammals appeared. All mammal brains follow the same basic structure we’ve seen in these images, with a well developed hindbrain and midbrain. However, the forebrain — specifically, the cortex — developed as mammals evolved.

As the cortex grows, it folds in on itself to conserve space, creating the wrinkles we see on human brains. The “hills” are called gyri and the “valleys” are called sulci. Mammals vary drastically in the size of their cortex and the amount of sulci and gyri, as shown in the brain photos below:

Humans and a few other animals we judge to be intelligent have the most sulci and gyri and thus the most densely-packed brain tissue. Their huge cerebral cortices give them the largest brains relative to body size.

There is no reason to think that the evolution of the cerebral cortex is complete, because its growth has shown no signs of stopping yet in living species. Perhaps some day, new species will evolve with cortices even larger and denser than our own.

There’s one more important part of brain evolution: the timing of the evolution of different parts of the forebrain.

Subcortical vs. Cortical Forebrain: Do Humans Really Have a “Triune Brain?”

There’s a popular theory called the “Triune Brain Theory,” which claims that:

1) Humans have three brain systems, a “lizard brain,” a “mammalian brain,” and a “human brain.”

2) The “lizard brain” is associated with the brain stem and cerebellum. It controls fight or flight mode, and behavior done unconsciously on “autopilot.”

3) The “mammal brain” is associated with the “limbic system” (the hippocampus, amygdala, and other forebrain regions buried within the cerebral cortex). These regions are known to govern emotions, memories, and habits. Our emotions give us the motivation to make decisions.

4) The “human brain” is associated with the cerebral cortex, especially the frontal lobe. It is associated with reasoning, language, abstract thought, imagination, and consciousness.

Apparently, this theory is popular in yoga circles.

What is true about this idea:

The brain stem and cerebellum reached full development before the limbic system, which developed before the cortex.

All mammals share roughly the same limbic system, but their cerebral cortices are very different.

The brain stem and cerebellum do coordinate the fight or flight response, and operate without our conscious awareness.

The limbic system does process emotions, memories, and habits, informing our decision making.

The cortex does enable language, reasoning and abstract thought, and imagination.

What is not true about this theory:

The cerebral cortex is not the “human brain”: It’s not unique to humans. It’s just especially well developed in primates and other mammals known for intelligent behavior.

These parts of the brain are not as separate and independent as the theory makes it seem. For example, our more advanced cognitive functions (language, music, math, reasoning, etc.) draw on the limbic system and cerebellum as well as the cortex.

What we can learn from this theory:

The limbic system was fully developed in early mammals, while the cortex continued developing up to the present.

In this way, too, the brain developed from the inside out.

TL;DR

Let’s compare the beginning and end of this journey using the brains of a rainbow trout and a human. See how much brains have changed over evolutionary time!

Here’s how:

Overall, the hindbrain developed first and the forebrain developed last.

First, the brain stem and a few sensory forebrain regions evolved. They can be seen in early vertebrates, like fish and lampreys.

Next, the cerebellum appeared, grew, and developed into the distinctive ridged two-hemisphere shape currently seen in birds and mammals.

The limbic system was well-developed by the time mammals evolved.

As mammals evolved, the cortex grew and folded in on itself, covering the limbic system and midbrain.

In short: The brain developed from back to front, and inside to out.