The Top 2 Ways Expertise Changes How You See

When you learn a lot about something, you look at it differently.

You’ve probably noticed that learning a new profession (like nursing) or a new hobby (like chess) changes the way people think and the vocabulary they use. But did you know it also changes how they see?

We know that because researchers in many fields (psychology, education, business, the military) often compare people unfamiliar with an area to those with knowledge and skill. For example, researchers compare medical students to doctors or chess players to grandmasters. [1]

The change in perception that comes with expert knowledge is called perceptual expertise. Perceptual expertise develops in all the senses. Musicians become sensitive to pitch and rhythm; chefs and food critics appreciate nuances of scent and flavor. However, we know the most about how perceptual expertise affects vision.

Two kinds of perceptual expertise are especially well understood.

First, experts are better at noticing and naming “objects of expertise.” For example, a birdwatcher can spot and name distant birds.

Second, experts learn complex visual patterns that would overwhelm most people.

These everyday “superpowers” have a catch: they’re limited to a person’s area of expertise, which can be surprisingly narrow. For example, a car expert who specializes in antique cars might develop perceptual expertise for antique cars but not modern ones.

Let’s delve deeper into how experts see the world differently.

Experts are better at noticing and recognizing objects of expertise

You’ve probably noticed that when you're walking down the street, what you’re thinking about changes what you notice. When you need a haircut, you suddenly start seeing hair salons everywhere. They were always there; you just didn’t pay attention to them until they became important to you.

Becoming an expert involves that effect, to the extreme.

For example, bird experts notice birds that blend into the background for everyone else.

Experts show their superior object recognition in the psychology lab. Herschler and Hochstein brought bird experts, car experts, and non-experts into the lab. They were shown photos of objects, including birds, cars, faces, and miscellaneous others, in large arrays – 25 objects were shown at once, and participants were asked to identify a specific object, which could be from any of the 4 categories.

For example, participants saw arrays like this one below:

Non-experts find all types of objects equally well. Car experts identify cars faster than other objects, and bird experts recognize birds faster than other objects.

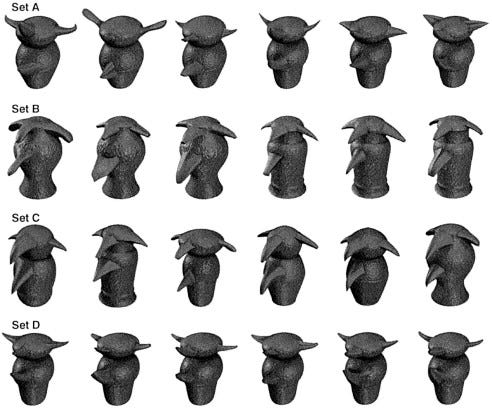

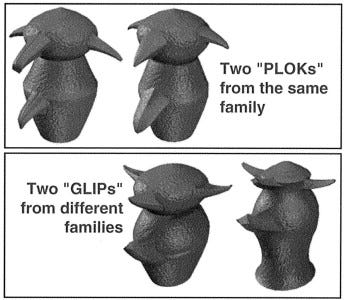

Researchers can create their own “experts” in the lab. Isabel Gauthier’s team designed artificial creatures called “greebles.” They taught people to name them and group them into categories. (These categories, called “families” and “genders,” were based on the angle and shape of various parts; see the images from the study below). These volunteers spent many hours training, although not the full “10,000” hours Anders Ericsson claims are necessary.

The images above and below show the greebles used in Isabel Gauthier and colleagues’ 1998 study, “Training Greeble Experts.” Participants learned to name and categorize individual Greebles. Participants saw Sets A and B right after finishing training, and sets C and D 8 to 13 weeks later (image 1, above). Greebles were grouped into “families” and “genders,” which differed in the angle and configuration of various parts (image 2, below).

After training, these “experts” see artificial creatures differently than do people who have never seen them before. The experts can name individual creatures and categorize them accurately.

They haven’t just memorized a set of names and images – they can accurately categorize artificial creatures they’ve never seen before.

How to Pay Attention Like an Expert

Have you ever wanted to better notice the surroundings you see every day, and learn to tune out?

To better notice the world around you, try walking in the shoes of an expert.

In her book “On Looking: Eleven Walks With Expert Eyes,” Alexandra Horowitz’ walks the same ordinary city blocks alongside people with different areas of expertise: urban sociology, geology, medicine, and sound design. Each expert pointed out different things, making each walk a unique experience.

If you can’t find an expert to walk with you, try imitating one. Focus on some aspect of your surroundings that interests you. That could be many things:

the changing colors of autumn leaves;

the architectural styles of buildings;

the species of wild and garden plants;

the breeds of dogs being walked;

birds and their calls.

Choose anything you enjoy perceiving, that makes you at least a little curious.

Now, take a walk somewhere you go every day, while focusing on whatever you’ve chosen. You’ll notice things that you passed by daily and never saw before. Your surroundings will become more interesting. You might even have questions about the architectural styles (or plants, birds, dog breeds, etc.) you see and look up the answers. If you become actively involved in the experience, you might develop expertise.

Even the most ordinary, seemingly boring scenery can become interesting when observed repeatedly. Claude Monet, best known for his paintings of water lilies, made a series of paintings of a haystack in a field. These paintings show the same haystack under different lighting, weather conditions, and seasons — and each one looks startlingly different.

The above image of Monet’s complete series of haystack paintings comes from an interesting analysis on the Electric Light Company blog.

Everywhere, at any given moment, physical, biochemical and social processes are happening, usually unnoticed. As mindfulness afficionados will tell you, when you tune in, you’ll find more change and complexity than you can imagine.

You might even lose the temptation to check your cell phone.

Experts Remember Visual Patterns

Many areas of expertise involve learning to recognize complex visual patterns. For example, chess grandmasters can look at an arrangement of pieces on the board and tell you which player is attacking and what each player’s next move is likely to be. They can even tell you what famous games involved this arrangement. (Some arrangements of pieces, called “positions,” are named, and chess experts learn them by name).

Chess experts see not only the placement of each piece, but also a meaningful whole defined by the relationship between the locations of the pieces.

Chase, Simon, and Gobet demonstrated this pattern perception by asking chess masters and ordinary players to remember the positions of many pieces after a 5 second delay. Some positions came from actual master-level chess games. Others were completely random, and probably wouldn’t occur in an actual game; they were intended to be meaningless to an expert chess player.

This experiment is shown in the image below, from a description of Chase, Simon, and Gobet's chess studies:

On the left is an example of a position from a real chess game. On the right is an example of a random position. Participants were asked to recall the position of all game pieces after a 5-second delay.

If chess experts know the meanings of whole configurations of pieces, then they should remember real game positions better than novice players do, but not random positions.

That’s exactly what the study found.

The research team tested the working memory spans of both groups. These were similar.

So, chess masters don’t remember arrangements of chess pieces better than novices because they’re better at keeping in mind large amounts of arbitrary information. Instead, they get around normal human working memory limitations by using their chess knowledge. Instead of remembering 15 separate pieces, they group several pieces’ relative positions into a meaningful “chunk,” which can then be recalled as a unit. This process is called “chunking.”

Working memory is quite limited —about 7 items plus or minus 2, on average. Three or 4 chunks will fit into that mental space, while 15 separate positions will not.

How to Remember Patterns Like an Expert

Chess is highly visual-spatial, but chunking can be applied to other kinds of information.

The next time you have to study, act like an expert and try chunking. Look for ways to group numbers, vocabulary, or other data into meaningful, memorable chunks.

If that’s hard, find an expert (or at least a more knowledgeable person) to help you understand and chunk the facts.

While this process takes time and thought, over the long term, it will make your studying more efficient.

Expertise in Everyday Life

When people develop expertise, it changes how they see. They come to recognize and pay attention to their objects of expertise and they remember complex spatial patterns.

These changes are the best-known ones, but others are also possible. Different areas of expertise — from sports to video games to interpreting X-rays — lead to different perceptual changes. The demands of the area of expertise determine what ways of looking are helpful.

The more we research different areas of expertise, the more kinds of perceptual expertise we will find.

In future posts, I may discuss more kinds of perceptual expertise. Research on “action video games” is especially interesting.

Everyone is an expert at something.

Literate people are experts at decoding, the process of looking at a string of letters and spaces and seeing words. Most people might be considered experts at recognizing faces. [2] Yes, even daily activities which we barely notice, like reading or recognizing people, involve expertise.

What sorts of expertise come up in your life?

Have you ever picked up a hobby, like an art, a sport, or an instrument, and later realized you saw the world differently because of it? What changed?

To share your thoughts and experiences with perceptual expertise, leave a comment here.

Footnotes

[1] Although researchers often compare experts to “non-experts” or “novices,” expertise is a continuum. In studies, “experts” range from typical competent members of a profession, such as doctors, to world-class performers, such as chess grandmasters.

[2] I feel obligated to mention that there is a debate over whether face perception is a type of expertise. Just as experts see their objects of expertise in a special way, so most people see faces in a special way. However, some researchers, such as Nancy Kanwisher, believe that humans are innately “wired” to perceive faces in certain ways. Others think we learn early in life through constant experience looking at faces, just as we learn other types of expertise through experience. Personally, I have little interest in the question. However, the debate has spawned a large, interesting, and potentially relevant line of research about how people perceive faces. Also, I am indirectly connected to participants in this debate (see full disclosure below).

Full disclosure: I used to research perceptual expertise. My masters thesis project investigated what sort of perceptual expertise children might develop when they are intensely interested in dinosaurs. My grand-adviser was Isabel Gauthier—the researcher with the greebles.

Mosaic of Minds is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.