How ChatGPT and Generative AI Will Affect Research With Humans

Science and medical researchers face privacy and consent issues.

Over the next year or so, expect to hear that ChatGPT and other generative AI are causing privacy issues for researchers who work with humans.

To understand why, we must know how researchers use data and what privacy issues come up.

It all comes down to consent

When you decide whether to participate in a scientific or medical experiment, a consent form explains what will happen to your data.

You are told where and how your data is stored, who will have access to it, and how it will be used. Often, you are asked to give permission for broad uses like training students or “presentations at scientific meetings.”

You will be told there is a small risk that your data could be hacked, stolen, or misused. You will be informed how the researchers guard against that possibility.

It will then be up to you to decide whether participating is worth the risk.

You have the right to informed consent: the right to decide what researchers can, and can’t, do with your data.

The two kinds of data

Whether they work in a university or a hospital, and whether they do basic psychology research or applied clinical trials, researchers follow the same basic process to protect your privacy while using your data.

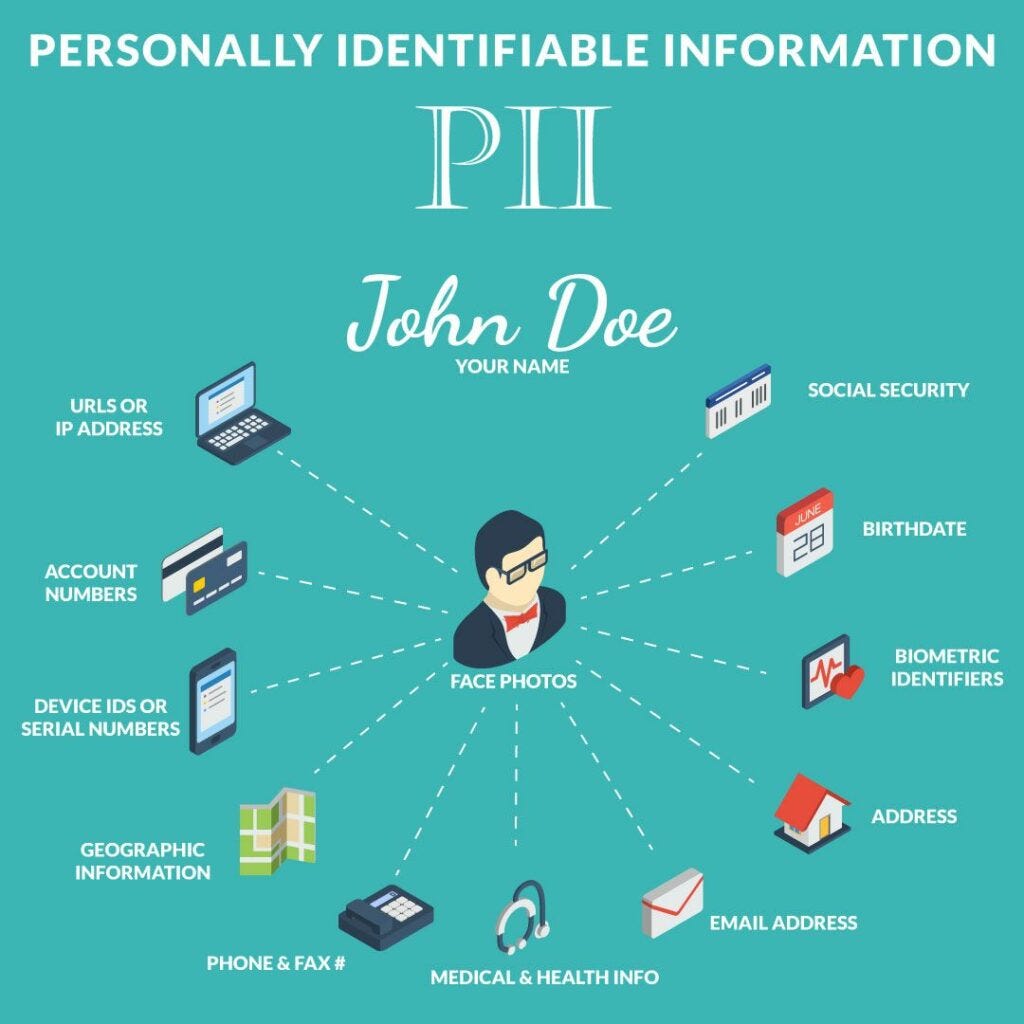

Researchers collect 2 types of data: “personally identifying information,” which could be used to figure out your identity, and everything else.

Identifying information is more than just your name. It can include:

Date of birth,

Contact information (Phone number, email, street address),

Social security number,

Hospital ID number,

Health insurance plan information,

Photos or videos collected during the experiment,

Unique biometric data, such as your DNA sequence.

Non-identifying information, from a research perspective, will include things like:

Age or age range (such as 4 years old or 50-59 years old);

Experimental results (reaction time, accuracy, neuroimaging scans, heart rate, blood pressure, etc.),

Socioeconomic status,

Race/ethnic group,

Sex and/or gender,

Broad location (minimum specificity is a region, such as “a university town in the midwestern United States”),

Medications taken,

Diagnoses, unless you have an extremely rare disease,

Standardized test data (working memory, IQ, memory tests),

Type of location where you receive medical treatment or therapy, if relevant (eg, “an outpatient clinic associated with a university hospital”).

As you can see, non-identifying information can be extremely sensitive. That makes separating it from identifying information imperative.

Researchers want to keep your identifying information as private as possible, while making the rest of the information as accessible as possible to other researchers and often, the general public.

Thus, researchers disassociate the data from identifying information about the participants.

That way, your boss won’t find out that, say, you’re trans, or have an opiate addiction, or are receiving therapy or taking Adderall.

Participants are assigned a code, or “identifier,” that refers to them in the experiment and any published data. The “identifier” will be some combination of letters or numbers that will be meaningful only to the researchers.

Any data collected during the experiment which does not identify a person is called “de-identified.” Such data is associated with participants’ identifier instead of their name.

There is always some sort of file, somewhere, that links the participants’ real identity with their identifiers. The risk that this information could be stolen or misused is an inescapable risk of doing research.

Consent forms explain in detail what sort of file exists, where it’s stored, who has access to it, and what measures have been take to keep it private. Generally, participants are asked to trust to the security of university or hospital networks and to locked filing cabinets to protect their privacy.

Participants’ privacy is only as secure as the methods for protecting that link between participants’ identifying information and their data.

Data has many lives

Much research, especially in medicine, involves contributing to a database shared by many research labs. When you contribute data to a research database, it won’t only be used for the study you actively participate in. It will be used for many other studies. Furthermore, you probably won’t be informed about who is using your data to research what questions, and you won’t get to sign a consent form each time.

When you contribute to a research database, you are giving broad consent for many unknown researchers to use your data for unknown purposes.

(That’s often not as scary as it sounds, and it’s not hard to discover how your data is being used. For example, a database called CHILDES collects audio, video, and text transcripts of young children speaking. Many studies of typical and atypical language and social development use the CHILDES database. This database is so vast, and has existed for so long, that it would be impractical to contact every participant about every study in which their child’s data is used. However, potential participants can access a clear, rigorous process for obtaining families’ consent and ensuring their child’s data is used responsibly).

Even before the advent of ChatGPT, participant data was being used ever more widely, for two reasons.

First, the open access movement has led researchers to start posting more data online. It wasn’t enough just to report the results of the statistical calculations. In the interest of accuracy and transparency, other researchers needed to be able to check these calculations. Thus, researchers started posting the de-identified data from each participant. Having access to individual data does more than just allow researchers to check each other’s work. It also allows any scientists looking at the data to perform their own analyses and draw their own conclusions, which may not have occurred to the original researchers.

The open access movement also champions making research accessible to as many people as possible, including non-scientists. As a result, people’s de-identified data is available to researchers and often the general public, worldwide.

That presents a big privacy problem.

Second, there has been increasing interest in using the many huge databases of medical information collected by governments and hospitals for health research. Research doesn’t always involve making people go to a lab and do something unusual; it can also consist of using the massive amounts of data collected anyway when organizations provide health care and process health insurance claims.

For example, your local hospital system might ask for permission to use your medical records from visits to your primary care doctor or specialists. They may also ask for information as personal and sensitive as DNA sequencing. And more researchers than just your local hospital system might be given access.

Do today’s consent forms acknowledge and adequately address these realities?

My hypothesis: such large-scale medical studies as the Illinois “All of Us” Precision Medicine study[1] carefully protect people’s data and clearly explain the potential risks of participating. However, my experience suggests basic research studies in psychology or neuroscience could be lagging behind.

In short, the advent of ChatGPT only adds to existing privacy issues.

Want to use your data to train an AI? No? Too late.

As machine learning algorithms like ChatGPT are used increasingly often, they create a new privacy concern: participants’ data could be used to train machine learning algorithms without participants’ knowledge or permission. That violates people’s right to informed consent.

Privacy concerns have been raised outside the research world. Earlier in 2023, the Italian government even ordered OpenAI to stop using citizens’ personal information without their permission. In Europe, GPDR rules protect identifying information, even if it is freely available online. ChatGPT and similar programs will run afoul of GPDR and other regulations. It won’t be long before research regulatory organizations start taking an interest.

Participants need to know whether their data could be used for machine learning, and they should have the opportunity to give or deny consent.

If OpenAI (the company behind ChatGPT) does not set such policies, researchers and their regulatory organizations should lead the way. Most likely, they will.

What’s next?

I predict that standard experimental consent forms will change in the next year or two to address new privacy concerns associated with generative AI.

I haven’t yet seen researchers discussing this privacy issue on social media, but they must be aware. Expect it to become a hot topic soon.

Change can happen slowly in academia. Participant concern will push researchers to act faster to protect their data.

If you participate in research, ask questions about whether machine learning algorithms will have access to your data, and how the researchers will protect your data from companies creating generative AI.

Always remember: you have the right to decide how your data will be used.

What do you think?

What effect is ChatGPT having on the research consent process? How aware do you think researchers are right now?

How do you think ChatGPT will change research in the future?

Have you seen any efforts to protect research participants’ privacy and right to consent?

To share your thoughts, click the comment button below.

[1] Full disclosure: I am participating in this study, and have consented to contribute some, but not all, of the data requested.