Suppose you give someone who reads poorly a book with print that is larger, darker, clearer, and more widely spaced – in other words, easier to see.

The sort of books that currently support people with low vision.

Will they read better?

When print is easier to see, it becomes faster and easier to decode (that is, recognize the words). But, is it also better understood?

You might think increasing visibility would make no difference. To comprehend a word, one must first decode it. Once decoded, however, it’s the same word no matter how fast or easily it was decoded, so why would the ease of decoding matter?

Alternatively, maybe easy-to-see print could help, indirectly. When people can spend less mental energy on decoding, perhaps they have more available for comprehension.

Some researchers would predict easier-to-see print could actually be detrimental. Readers, realizing that decoding is easier, might pay less attention to the whole process of reading. Inattention often worsens comprehension.

The question matters because Americans are bad at reading.

According to The Literacy Project, the average American reads at the 7th- to 8th-grade level. [5]

Half of U.S. adults can’t read a book written at the 8th-grade level. [4]

Thus, the American Medical Association, National Institutes of Health and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention say that medical information for the public should be written at no higher than an 8th-grade reading level.

That makes it harder for Americans to:

understand and think critically about the news;

understand legal documents; or

research their health conditions.

Could making text easier to see be a simple way to make people a little healthier, wealthier, and wiser?

What Happens When You Give Students Easy-to-See Books?

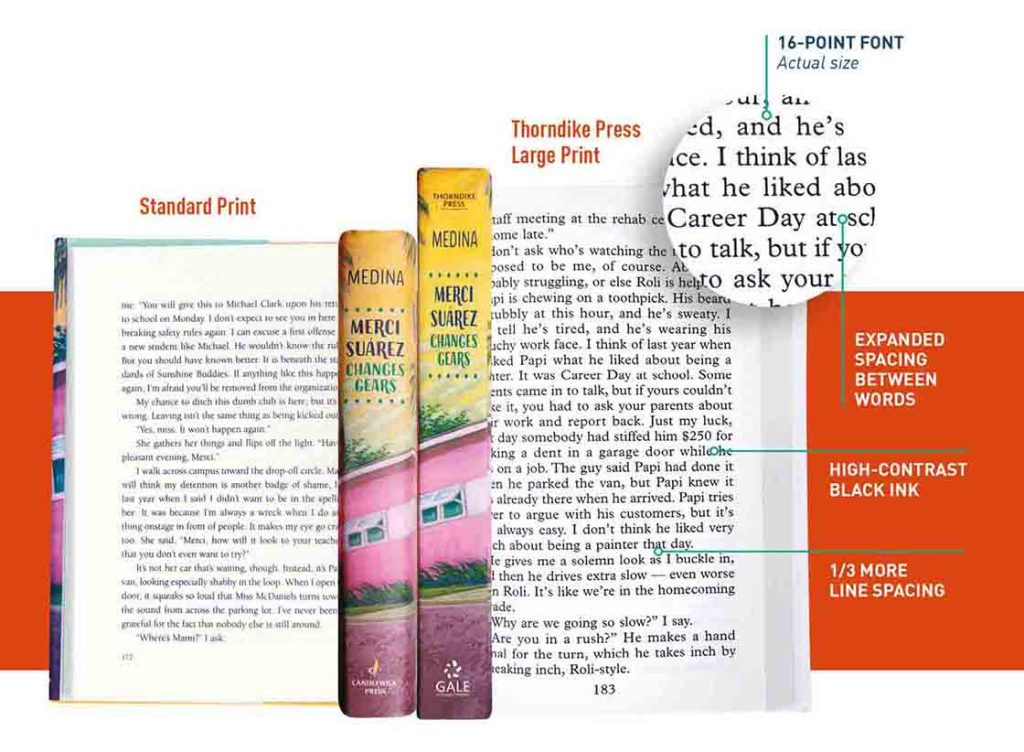

Enter Thorndike Press, which publishes large print books. In addition to bigger font (16 point), these books include high contrast and extra spacing between words and lines.

Yet, to prevent stigma, the text and cover look almost identical to the standard version.

Thorndike Press partnered with 15 American schools to test how these books affected students and teachers.

Participants: 1696 students in grades 3-12, and 56 teachers and librarians.

Schools: Fifteen American schools, all Title 1 schools (schools receiving federal funding due to a high percentage of students from low income families). They were located across the country, with 9 in urban areas, 4 in suburban towns, and 2 in rural areas. Two thirds of the schools (10/15) had over 50% African American or Hispanic students.

Book Selection: Researchers provided several popular, age-appropriate children’s fiction and nonfiction books to schools, including The Outsiders, I Am Malala, Salt to the Sea, and Hatchet. Teachers incorporated the books into their usual teaching practices.

How Results Were Measured: All schools provided results surveys, focus groups, and interviews, comparing students who read large print to those reading the same book in standard print. Three quarters (12/15) of the schools also provided student achievement data for the 2 groups. As different schools measured reading achievement in different ways, the results are reported in a fragmentary way, describing several schools separately as detailed “case studies.”

So, what did the study find?

Not surprisingly, students and teachers liked Thorndike’s books better than standard books, and wanted to use them in the future.

Students also said they paid more attention to the large print books. If they were observing themselves accurately, that contradicts some researchers’ hypothesis that they would pay less attention.

How well did students understand Thorndike’s books?

Liking and attending to books matters, but doesn’t imply anything about understanding.

First, a little background: many of the study results are based on “lexile scores”. Lexile is a scale used to measure a student’s reading comprehension skills or a text’s difficulty, on a scale ranging from 0L to 2000L. Lexile scores measure both using the same scale, allowing readers to compare their reading ability to a book’s difficulty to choose a book at an appropriate difficulty level. (That’s often defined as the lexile score at which a reader can understand 75% of a text without assistance: easy enough to mostly understand, but hard enough not to bore).

Whenever struggling students reading large print books were compared with peers reading standard books, the large print readers improved their reading comprehension more over the course of the school year. We find the same pattern regardless of grade level or school demographics.

Sometimes, the gap is impressive. For example:

At an urban elementary school in Texas, 3rd graders (97% Hispanic, 65% English language learners) originally read a year behind. During the study their lexile level increased by 120 points (342 to 462). That brought them up to grade level.

At an urban middle school in Texas, 6th-8th grade students all read well below grade level at the beginning of the year. Those who read large print books increased in Lexile reading level by 2-3 times the national average. Specifically, those who read large print gained 149 points (6th graders), 228 (7th graders), and 142 (8th graders), compared to a national average of 70.

These results suggest students benefited from large print books throughout the school year.

Thorndike Press attributes students’ success to increased motivation, interest, and confidence in their own reading skills. That seems plausible, although the causal relationships weren’t directly tested in the study. Perhaps further studies can disentangle why large print books help students understand what they read.

For our purposes, what matters is that they do help. Furthermore, English language learners and students with disabilities benefit, too – which isn’t always true for educational “interventions”.

How did you think this experiment would turn out? Did anything surprise you?

Have we found a new “curb cut?"

If easier to see means easier to understand, what would happen if we applied this principle more broadly?

What if books, magazines, newspapers, brochures, forms, menus, show programs, doctor’s instructions, and webpages were all as clearly formatted as Thorndike Press’ books?

What if large, widely spaced print wasn’t just for people with low vision? What if it was the norm for everyone?

Text is so ever-present in our lives that this might be the ultimate curb cut effect. In other words, high-visibility text could be a case where making disability accommodations ubiquitous helps everyone, in the same way that curb cuts for people in wheelchairs make walking easier for everyone.

Furthermore, making such formatting changes would probably be fairly easy and cheap.

Would Americans then read better, or even think more critically about what they read?

That remains to be seen. Let’s find out.

…

What has your experience been with reading extremely clear or unclear text? (Both are everywhere, on the web and in physical space).

What conclusion would you draw from this research?

Want to delve deeper?

Here’s the blog post that alerted me to this research and inspired this post. It’s by Sabine McAlpine at YA Books and More.

If you want to learn more about Thorndike Press’s study, you can find the details here.

You can also compare children in the Thorndike Press study with their same-grade peers nationwide, using these Lexile Grade Level Charts. These show the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentile scores at each grade level.

You might also be interested in…

…how the brain changes as we learn to read, and how that differs in people with dyslexia.

Emily, thanks for your fascinating analysis of the research. The Texas case studies showing 120-228 point Lexile gains through large print adoption support a thesis about cognitive load redistribution. I’m particularly intrigued by how the reduced decoding effort might be creating a virtuous cycle – as comprehension improves, students experience more reading success, further boosting engagement. I like your curb-cut effect analogy that text accessibility features could help all readers, not just those with visual impairments. This research deserves greater consideration in education policy, especially for populations facing linguistic or cognitive barriers. Thank you!