Disabilities are Created by Culture and Technology

Imagine a person with a reading disability who reads slowly and effortfully. Text surrounds them constantly, demanding to be read: news articles, emails, work documents, tax forms, user’s manuals, street signs, and menus.

This omnipresent text puts people with reading disabilities at a disadvantage.

Now, imagine the same person, with the same brain, living in a culture that has no system of writing. Does that person have a disability?

That person would have no more difficulty than anyone else. They wouldn’t even be noticeably different.

They wouldn’t have a disability.

Similarly, in cultures where people are expected to sit still for hours, hyperactivity impairs people. However, in a nomadic hunter-gatherer society, it might be harmless, or even beneficial.

Examples like these show that a disability is more than the characteristics of a person's brain and body. A person's environment is an integral part of the disability.

A disability happens when a person's physical capabilities mismatch with their environment, putting the person at a disadvantage. For example, a reading disability “mismatches” with a text-heavy culture.

Let’s unpack what a person’s “environment” means.

What’s an Environment?

An “environment” is the culture, space, and time in which a person lives. It includes:

institutions (for example, the way schooling works),

the built environment (such as architecture and city planning),

cultural practices (such as values and politeness norms), and

the available technology.

Let's delve deeper into how culture and technology create disabilities.

Technology

Let's start with technology, perhaps the easiest aspect of culture to pin down.

Two types of technology affect people with disabilities: that used by the whole culture (such as writing or computers), and “assistive” technology specifically for people with disabilities (such as Braille).

Mainstream Technology

As humans develop new technology, they must develop new skills for using it. Those who learn these skills fastest and best will be seen as talented.

A person who wouldn’t have stood out in, say, medieval England can become a 21st century computer “whiz.”

However, new technology also creates disabilities. After all, if there can be computer “whizzes,” there must also be computer “dunces.”

In other words: the more technologies and specialized jobs a culture has, the more kinds of disabilities it will have.

Inevitably, there will be more opportunities for mismatch, and thus more disabilities.

Assistive Technology

Assistive technologies determine what people with brain or body limitations can accomplish.

They vary in how “high tech” they seem and how easy they are to obtain. Examples include:

Wheelchairs,

Sign languages,

Closed captions,

Curb cuts,

Prosthetic limbs,

Hearing aids,

Glasses.

People can be disabled when their culture lacks the assistive technology they need. Additionally, they can be disabled when the technology exists, but the culture doesn’t offer access.

For example, some people can't speak, for a variety of reasons. They were once assumed to have nothing to say. For that reason, the word “dumb” once meant both inability to speak and “stupid.”

Today, various technologies can help mute people express themselves: sign languages, writing systems, speaking technology of the sort Stephen Hawking used, and more. These are called augmentative and assistive communication (AAC) methods. Until relatively recently, however, few such methods existed.

For example, formalized sign languages developed surprisingly recently: French sign language in a Parisian school for the D/deaf founded in 1755; American Sign Language in the American School for the Deaf founded in 1817. Although British records of sign languages go back to at least the 1500s, and British Sign Language (BSL) as we know it probably emerged in the late 19th century, it wasn’t recognized and named until 1975.

Without a formalized sign language, children cobble together a system of “home signs" with their families and other hearing people. Home signs communicate much more than speaking people’s gestures do, but lack the grammar and full resources of a true language. When groups of D/deaf people interact, they gradually create a language, which starts out much like home signs and gradually becomes more like a formal language. Learning a true sign language early in life prevents people from having to "reinvent the wheel” this way.

To use AAC to communicate, one must be able to learn the system and own any devices required. In the past, people rarely thought to teach mute people an AAC system. Even today, surprisingly little has changed.

Gatekeepers, especially in schools, sometimes create a Catch-22 where children must demonstrate the ability to communicate in order to get the technology they need to communicate. Teachers and speech therapists with low expectations force to mute people to use insufficiently-flexible technology that further limits their ability to express themselves.

Thus, to understand an individual’s technological environment, we must consider both the assistive technology that exists in a culture and the individual’s opportunity to access it.

Stay tuned for more about assistive technology in upcoming posts in this series. For now, keep in mind that low expectations and limited access to assistive technology reduce what a person can do, without anything about their brain or body changing. Thus, to measure a person's functioning, in research or clinical practice, we must consider the technological context.

The Built Environment

The built environment is the physical space in which people live. It includes factors like lights, sounds, and traffic.

Public Spaces. Public areas full of comfortable seating are especially important for people who experience pain, fatigue, stiffness, or tremors while moving. Stopping and resting in public places can make it possible for some people to walk without a mobility aid. It also helps people without disabilities who fatigue easily, such as elderly or pregnant people.

Public areas with available restrooms help people with conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or nausea.

People with anxiety, PTSD, or various mood disorders also retreat to restrooms to ground themselves and manage emotions.

Thus, when cities make public places uncomfortable and restaurants lock their bathrooms to deter homeless people, they’re also pushing away people with disabilities.

Noise and Crowds. For people with hearing impairment or auditory processing disorder, loud music in public places can interfere with participating in conversations. In some restaurants, I struggle to understand others sitting just across the table.

Nightlife in particular can be inaccessible to young people with disabilities, between the background music and the people shrieking over it. In some professions, that can interfere with socializing with coworkers. It can also close off options for socializing and dating in general. And it can induce a sense of “missing out."

Crowds can induce stress in people with sensory processing sensitivity or a history of trauma. When people sense their personal space constantly being invaded, they feel increasingly uncomfortable and even defensive.

Crowded grocery stores and malls can make shopping an exhausting ordeal. Discomfort with crowds prevent people from attending enjoyable social events they would otherwise attend–concerts, festivals, travel, etc.-- which others may misinterpret as being unsociable or uninterested.

When people know going to a crowded place will be tiring and uncomfortable, they may dread it. What starts as a simple processing sensitivity can turn into anxiety or even agoraphobia.

Unfortunately, most people don’t know that some people experience sensory stimuli more intensely, and that it can produce anxiety and fatigue. Thus, they, and any therapists, may assume that the ultimate cause is a mental illness. That diagnosis may be incorrect– especially early in life, before the person has spent years developing intense dread, avoidance, and shame.

Office Architecture. Many neurodivergent people express discomfort with a recent workplace trend, the “open plan office." In these offices, multiple people work close together in one large room, often without so much as a cubicle between desks to block distracting sounds and visuals. You're stuck listening to your coworkers chewing gum, smelling their perfume, and watching them toss colorful stress balls around as they loudly gossip about office politics.

Although employers adopt an open office plan hoping to increase discussion and collaboration, it distracts and overwhelms employees instead, especially neurodivergent people. Neurodivergent workers end up doing the opposite of what the designers intended: blocking out stimuli using headphones and similar technology.

In short: cultures often build public places and offices in ways that handicap some people.

Culture and The Social Environment

How diverse and specialized are social roles? That is, is everyone a farmer, or are there many professions and lifestyles?

The more specialized roles a culture has, the disabilities it will recognize.

Child rearing practices: Who spends time with children, and how are they raised?

What behavior is expected and considered "socially skilled" at different ages?

How do people react to deviations from the norm?

Children with disabilities may function better in cultures that are tolerant of individual differences and treat them patiently rather than punitively.

Attitudes towards disabilities: The social environment also includes how the culture talks about and treats people with disabilities. What attitudes does the culture have?

Are people with disabilities included or isolated?

Do people try to "cure" or ameliorate disabilities, and if so, how?

The more people with disabilities are accepted and included, the more they thrive.

Amount of Independence vs. Interdependence: All humans require support from others, but the amount of help we need to function in everyday life differs between cultures. Cultures also vary in how negatively they judge those who need the most help.

People with disabilities tend to be less independent than others of the same age. That puts them more at risk in some cultures than others.

In present-day American culture, where the basic family unit is a nuclear family of parents and a few children, many parents worry about how their disabled children will fare after they’re gone.

In other times and places, parents and their children can receive support from multigenerational households or large extended families. In some areas, people have close relationships with their neighbors, or with members of their house of worship. In such communities, people with disabilities can give and receive support from more than just their parents, their siblings, local charities, and government services.

The work environment: What jobs does a culture have?

How are people hired? Does one have to pass job interviews, and if so, what skills do you need to succeed? How important are social connections versus job skills or educational background?

What laws or cultural norms prevent discrimination against job applicants or workers with disabilities, if any? What laws, if any, protect workers’ rights?

People with disabilities function best when they can get jobs that match their strengths and weaknesses; when social skills matter less than job skills; and when legal protection exists for workers with disabilities.

…

In short, people can have disabilities because of their culture, its technology, or its built environment. That means people can become disabled in many ways.

On the other hand, it also means we have many potential “levers” to change people’s environments and improve their lives.

Disability versus Impairment

Because a person’s environment helps create people’s disabilities, a disability is not a permanent, lifelong state of constant severity. It can be more or less of a problem depending on a person’s environment.

A child may be able to pay attention and complete his schoolwork with one teacher, but not another.

A person’s abilities might be good enough to meet the demands of home, but not school; or for high school, but not college. Many people are diagnosed with ADHD during the transition from high school to college. Without the structure from parents and teachers they depended on in high school, they flounder.

When changes in people’s environments overwhelm their ability to cope, their disabilities may become more severe, or even become visible for the first time. ADHD expert Laurie Dupar calls this sudden crisis a “tipping point.”

Disabilities can appear because many life changes, some of which are positive:

● The physical environment (such as moving to a new house);

● Life roles (switching to a new level of schooling or being promoted at work);

● Family dynamics (the birth of a new baby);

● Physical health (menopause);

● Sleep (prolonged sleep deprivation);

● Technology usage (phone or internet usage that disrupts analog organizational strategies without offering a digital replacement).

Some of these factors, such as sleep deprivation, directly reduce what a person can do. Others, such as moving or changes in technology usage, can affect a person without changing their basic abilities.

Thus, a person’s disability can come into being or become more severe, without anything about their abilities changing — if their environment places new demands on them or prevents them from using effective coping strategies.

If Culture Creates Disabilities, What Can We Do About It?

Humans live with many diseases (such as Parkinson’s) or impairments (such as inability to speak). If the culture, technology, and built environment put them at a disadvantage, these people become disabled.

However, a disease or limitation is not the same thing as a disability.

A disability is a mismatch between a person and their environment.

That means there are 2 ways to remove disabilities. The one that occurs to most people is curing the disease or getting rid of the impairment. One can also change the person’s environment so they can do more with the body they have. Ideally, we do both.

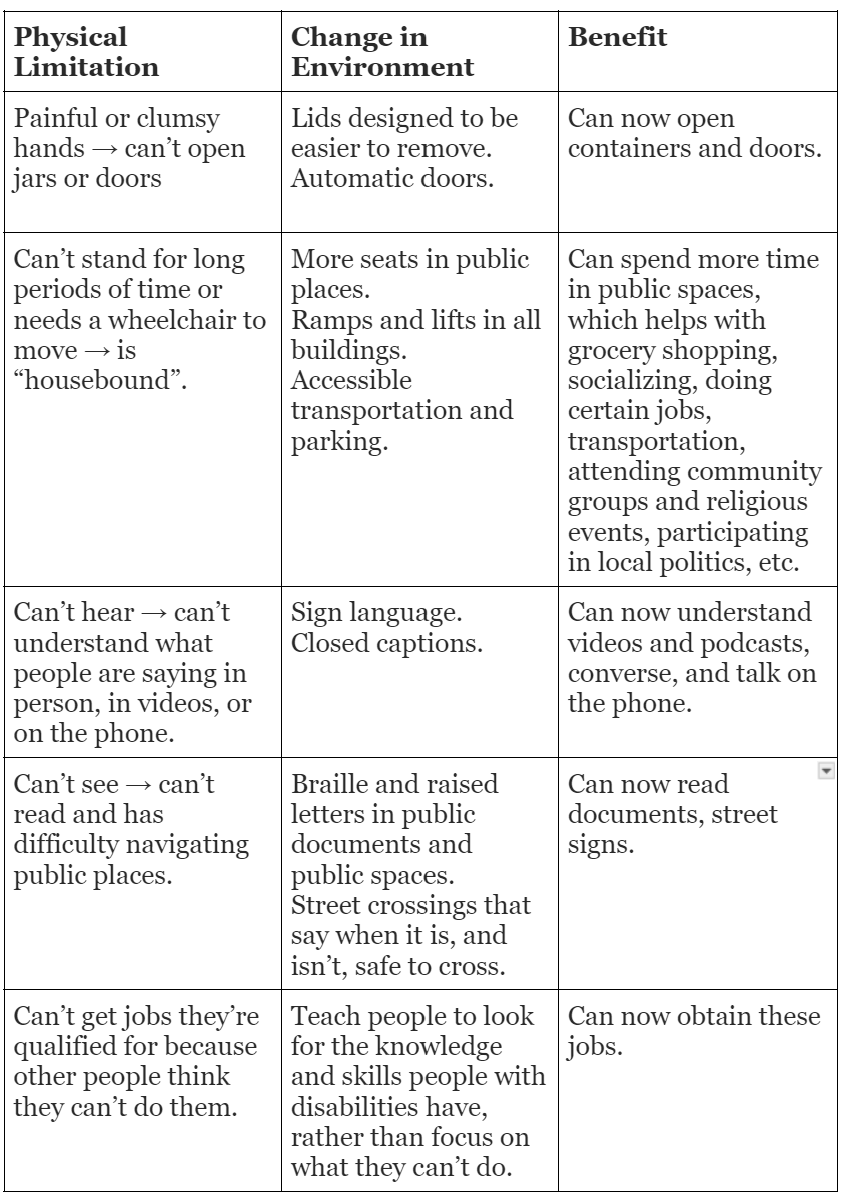

The table below shows ways we can make people's environments more enabling.

People seem to assume it’s always easier to change social factors than biological ones. However, people’s habits and cultural practices can stubbornly resist change. Changing people’s environments is easiest when it requires small, inexpensive changes that don’t stand out as “just for people with disabilities.” Such changes include:

allowing people to wear headphones in a noisy office, or

including closed captions on all media in classes.

When deciding what to change about a person’s body or environment to help them function better, I would do whatever creates the greatest improvement at the moment.

Want to learn more about how to create better environments for people with disabilities and why it matters? This approach to disabilities is called the "social model of disability.” Look up this idea to find both philosophy and practical advice.

What do you think?

Have you seen culture or technology disable anyone?

Does it help you to focus on improving your environment, or someone else’s?